My child has imaginary friends – is that normal?

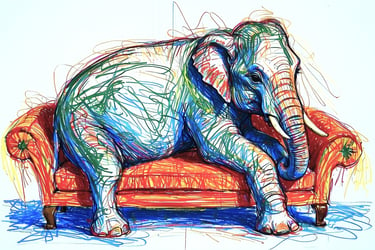

Imaginary friends, like Ruby’s elephants, are well-known in psychology today. Approximately 65% of children develop interactions with imaginary friends by the age of 7. [1] Previously, scientists held a negative view of imaginary friends. However, as the topic was researched more intensively, it was discovered that children actually benefit greatly from having imaginary friends.[2] Today, imaginary friends are considered a normal part of child development. Some scientists have been trying to break down prejudices against playing with imaginary friends for years. They found that all children with imaginary friends studied in studies were normal children and adolescents who were even measurably superior to same-aged children without imaginary companions in many areas."[3]

Children with imaginary friends have been shown to have, compared to children without imaginary friends:

· Higher creativity

· Better language skills

· Better social skills

· Better cooperation with other children

· More positive affective expression (i.e., better mood, emotion, motivation)

· Better empathy and role-taking abilities [4] [5]

· Less shyness[6]

Developmental psychology also views imaginary friends positively, for example, as 'helper egos.'[7]

It is very useful and reassuring to recognize the positive potential of these imaginary friends. Because imaginary friends enable learning processes and mental experiments that are simply not possible with normal friends. [8] Unlike real friends, Ruby's invisible elephants can be tailored exactly to individual needs. And of course, it's fun to be accompanied by invisible elephants and to discover yourself and the world from other perspectives. Of course, this does not mean that imaginary friends should replace real friends."

Even children, and of course adults, who have never encountered invisible elephants, can learn to apply and develop the concept of imaginary friends.[9]

How to use Ruby's elephants to empower children and train their skills

Practicing social interactions:

Children have conversations with their invisible elephants, the Ewaijas, play role-plays, and practice how to behave in social situations.

· Let's teach our Ewaija how to be a safe biker! What should we tell him to watch out for?

· The Ewaija doesn't understand why he can't eat more sweets today. Can you explain it to him in a way that won't cause any trouble?

· Two Ewaijas want to play, but one is feeling left out. What can we do to help them be good friends?

· The Ewaija always wants to be the first one through the door. If he doesn't make it, he gets upset. Talk to him about this situation and explain everything you think is important so that there won't be any trouble in the future.

Imaginary friends serve as a valuable tool for emotional processing in children.

By sharing their feelings with these imaginary companions, children develop their emotional vocabulary and learn to regulate their emotions. The act of verbalizing their emotions can be therapeutic in itself. Furthermore, imaginary friends can function as a safe space for children to explore difficult emotions and fears, fostering resilience and empathy. Through these interactions, children develop the capacity to take the perspective of others, a crucial skill for effective social interactions.

· Why is the Ewaija afraid of the dark? What can we or the other Ewaijas do to help him feel less scared?

· The little Ewaija has to go to the doctor, but he doesn't want to. Why is that? What can you tell him to make his doctor's visit easier?

· The Ewaija is angry because I sat on the spot he wanted to sit on. How can we handle this situation well?

· The child can also simply take the Ewaija with them so that they don't feel alone. This works especially well for abstract fears.

· Many children want to be a role model for the Ewaija, especially since the child is much more familiar with the human world.

· The Ewaija dropped his ice cream on the dirty floor, how does he feel now? What could we do to cheer him up? Should the Mamaewaija buy a new ice cream, or not? If yes: What does the little Ewaija learn from the situation? If no: How does the little Ewaija feel then and how could the Mamaewaija react? How does the Mamaewaija feel in this situation?

Self-reflection:

The child "educates" the Ewaija and thus themselves at the same time. Here, the educator can present all kinds of everyday problems as problems of the Ewaijas and have the child solve them.

· The Ewaija doesn't want to clean up his room. Let's teach our Ewaija about the importance of keeping our room tidy and show him how to clean up properly.

· Dinner time is a special time. What rules are there for dinner time in the human world and why are there these rules?

· The Ewaija has just watched you, explain to him what happened.

Role model:

The Ewaija can demonstrate positive behaviors and thus also be a role model for the child.

Strengthening self-confidence: Children can try out their abilities with their imaginary friend and affirm themselves.

Example: The child has painted a picture and proudly shows it to their Ewaija. The parents praise the picture and ask the elephant what he thinks of it.

Effect: The child feels valued and encouraged to further develop their creativity.

Developing problem-solving skills:

Children find solutions and hypotheses for problems that arise in situations with the Ewaijas.

· The Ewaija wants to come to kindergarten with you, but he doesn't fit through the front door or into the car. How can the elephant get to kindergarten?

· The Ewaija has fallen into a hole. How can we get him out again?

· The Ewaija has a big problem! He's lost his favorite toy. How can we help him find it?

Communication skills: In conversations with their Ewaija, children practice expressing their thoughts and feelings clearly.

· A child tells their Ewaija about their day or a particular situation. Suggestions: Did the Ewaija understand everything you told them? What questions does the Ewaija ask about it? Can you describe it more simply and accurately for the little Ewaija?

· Tell your Ewaija about your favorite food. Use words that describe the taste, smell, and texture.

· Tell your Ewaija how to make a sandwich. Use clear instructions

Fantasy:

Children develop complex stories and build entire worlds around the Ewaijas. They follow their own, mostly logical rules and systems. Actively help them, listen to them, and ask many specific questions about it. Parents should take the child's fantasy world seriously and respect their ideas.

Development of visualization:

Inventing an imaginary friend requires an active use of visualization.

· Close your eyes and imagine what your Ewaija looks like. Is it big or small? What color is its fur or skin? Does it have any special features? Does your T-shirt fit the Papaewaija?

· Imagine a world where Ewaijas live. What does it look like? What kind of plants and animals are there?

· Draw a picture of your Ewaija. Be sure to include all of their special features.

Comfort:

Studies show that many children can find comfort in invisible friends during challenging times.[10]

Having an imaginary friend can help children feel less alone and more secure.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this text is intended for informational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for professional advice. While imaginary friends can be a valuable tool for child development, they cannot address underlying emotional or psychological issues. If you notice any of the warning signs, such as excessive reliance on the imaginary friend or difficulty distinguishing between reality and fantasy, it is recommended to seek professional help.

Impressum

Titz Jan (2024): My child has imaginary friends – is that normal? Published under www.rubys-elefant.de Info@rubys-elefant.de, Bauernstraße 9, 29473 Göhrde, Germany.

[1] Binns, Corey (2006): Imaginary Friends and Enemies All Good, Scientists Say. livescience.com.

[2] Jiménez, Fanny (2015): Ihr Kind spielt mit erfundenen Freunden? Gut so! Psychologie. Welt.de.

[3] Seiffge-Krenke, Inge (2000) Ein sehr spezieller Freund: Der imaginäre Gefährte. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie 49, 9, S. 689-702.

[4] Ebd.

[5] Taylor, Marjorie (1999): Imaginary companions and the children who create them. New York, N.Y.: Oxford University Press.

[6] Taylor, Marjorie (2003): Children's imaginary companions. Special english Issue No. 16/2003/1: Childrens's Fantasies and Television, International Central Institute for Youth- and Educational Televizion.

[7] Binns, Corey (2006): Imaginary Friends and Enemies All Good, Scientists Say. livescience.com.

[8] Gleason, Tracy R. (2017): The psychological significance of play with imaginary companions in early childhood. Learn Behav 45, 432–440.

[9] Davis, Page E. Imaginary Friends: How imaginary Minds Mimic Real Life. In: Anna Abraham (2020): The Cambridge Handbook of the Imagination. Cambridge University Press.

[10] Seiffge-Krenke, Inge (2000) Ein sehr spezieller Freund: Der imaginäre Gefährte. Praxis der Kinderpsychologie und Kinderpsychiatrie 49, 9, S. 689-702.

IMPRESSUM

Jan Titz, Bauernstraße 9, 29473 Göhrde

ISBN 978-3-00-079270-0 Querformat

ISBN 978-3-00-080660-5 Hochformat

© 2024. All rights reserved.